We were walking up a steep hill last month and John starts chuckling. “You know, sometimes I just giggle, realising I’m doing this.”

It’s two and a half years since his double lung transplant, and walking up a steep hill is now kind of normal, although we try not to take it for granted.

It’s #OrganDonationWeek, and I’m reminded – as if I could forget – that a transplant is not the end of a journey but the start of another very different one.

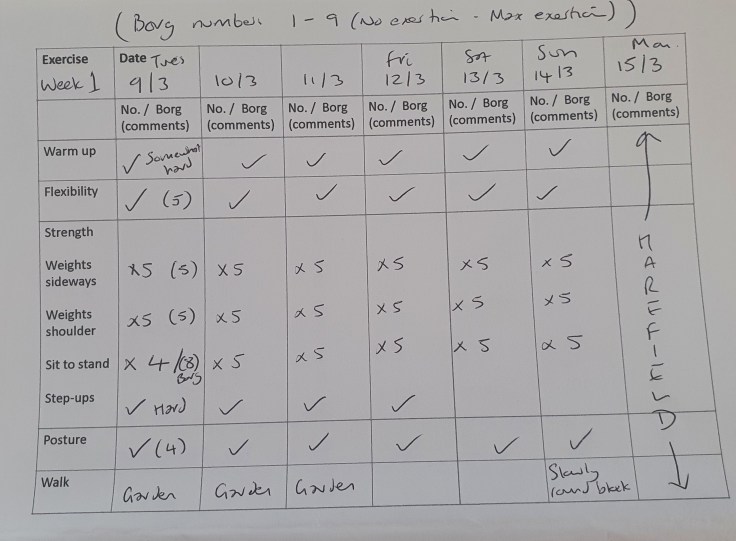

For the first 12 weeks after John came out of hospital, I became his personal trainer as we did his daily rehab programme at home together. From four sit-to-stands in a minute in the first session to 24 at the end of week four, he made steady progress.

This was interspersed with regular trips to Harefield Hospital to check his med levels and the impact they were having on the rest of his body while ensuring his new lungs were not rejected.

Meds are continually adjusted to find the right balance between suppressing the immune system enough to avoid rejection, but not too much to risk being unable to fight infections. And all while ensuring their toxicity is not causing havoc to other parts of the body.

Daily at-home monitoring, record-keeping and regular hospital tests gave John loads of data, which he loves, but he was a bit disappointed when a consultant told him that finding the optimum med levels is more of an art than a science.

Psychology of post-transplant life

The habits and psychology of post-transplant life take time to adjust to.

On the one hand, it’s a good thing when the frequency of hospital appointments is reduced – that means you’re fairly stable. On the other, there’s comfort and assurance in being frequently tested and monitored in a specialist hospital.

In the first few months especially, John’s anxiety about any possible sign of organ rejection was understandably very close to the surface. Those antibody levels are high!

I had to find the notes I’d taken during his last appointment and read out the consultant’s comments twice to him: it’s all normal, nothing to worry about. Look what I wrote down!

(Always, always, take notes – the information is often too much to fully process during the appointment.)

On the one hand – you’ve got this chance of another life so what are you going to do with it? On the other – avoid infections, stay on top of your med/monitoring regime, exercise regularly, keep your fingers crossed, don’t step on the cracks.

From motorbike to badminton

I was acutely aware that official survival rates are measured for 90 days, one year, and five years, and I confess to counting down to the 90 day mark as if it had some magic power. In some ways it does – if a person reaches 90 days in good health, they’re obviously more likely to live a lot longer.

And the longer time goes on without alarms – he’s only had one real setback, and that was two years in – the more confident you feel about doing stuff. So John’s back on his motorbike, back playing badminton, including at this year’s transplant games, which was a big target for him when he was in hospital.

I’m back at Spurs, and we’re back to going abroad for holidays. The days of hand luggage only are over, though, as his carry-on bag is full of medication.

And we’ve learned to start each holiday with a couple of days in a city just in case some important medicines are inadvertently left behind, as happened on our first trip away to Greece (forever grateful to a lovely pharmacist in Ioannina).

It can feel fleetingly strange to be back to the kind of life we had before the illness that led to his transplant – like, shouldn’t we be doing something more dramatic and daring with this second chance? – but that was the life we enjoyed, and missed when he was ill.

Toxic impact

We know we’ve been very lucky, and John’s story is not the same as many others.

We have friends who have endured serious complications in the immediate aftermath of their transplant, or who have developed complications in the first year or two, resulting in more admissions to hospital, more operations, more uncertainty.

The anti-rejection medication regime can have a toxic impact on the body, causing kidney damage, cancers, uncontrollable high blood pressure, diabetes.

American heart transplant recipient Amy Silverstein wrote brutally about this shortly before she died, calling for newer and safer transplant drugs, which haven’t changed much in many years.

“My first donor heart died of transplant medicine’s inadequate protection of the donor heart from rejection; my second will die most likely from their stymied immune effects that give free rein to cancer.”

She also talks about what she calls the ‘gratitude paradox’: the risk of and guilt about sounding like you’re complaining when you’ve already received the chance of a second life:

“Because a transplant begins with the overwhelming gift of a donor organ that brings you back from the brink of death, the entirety of a patient’s experience from that day forward is cast as a ‘miracle.’ But this narrative discourages transplant recipients from talking freely about the real problems we face and the compromising and life-threatening side effects of the medicines we must take.“

(‘Miracle’ is the way I described our own experience in the immediate aftermath of John’s transplant.)

Ultimate wish list

And we know people who have died waiting for a transplant.

There are more than 7,000 people on the entire organ transplant list – the word ‘list’ really doesn’t convey the stress and trauma associated with waiting for a transplant – but only about 1,400 donors a year (this does not include living donors).

According to the latest NHS Blood and Transplant annual report, transplant waiting lists are now down to levels last seen in 2014. Last year 439 patients died while waiting for a transplant and another 732 were taken off the transplant list, mostly because of deteriorating health.

Only 1% of people who die in the UK every year die “in the right circumstances and in the right location” to be eligible for their organs to be used to save someone’s life. And even then, organs might not be the right ‘match’ for the potential recipient – the proportion of lungs found suitable after they are donated is less than 20%.

That’s why we need as many people as possible to sign the organ donation register.

The undying gratitude – the living gratitude – of recipients for donors and their families, who make generous decisions in a time of grief, is immeasurable.

Leave a comment